Git Workflow

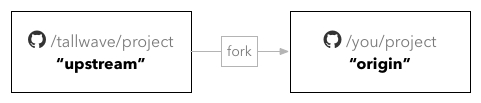

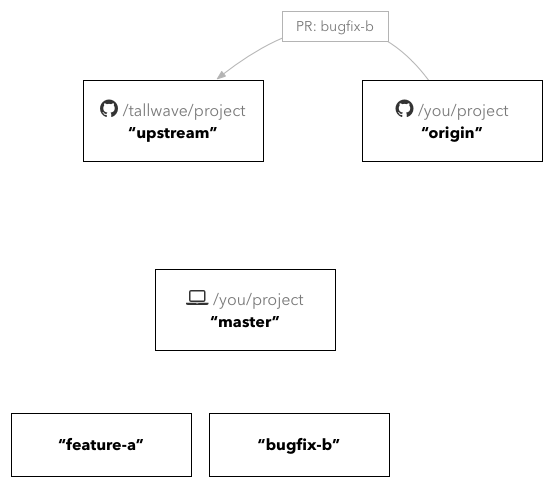

We follow a “fork and pull-request” model of software development. At a high level that means that everyone should fork the main repository and have their own version. This allows each developer to have a sandbox to play in without worrying of screwing things up for anyone else. It also means that if you do break everything completely, you can delete it all and fork it again.

Here’s how it works:

- Fork the main or

upstreamrepository. Now you have your own version of the repository. This is youroriginrepo.

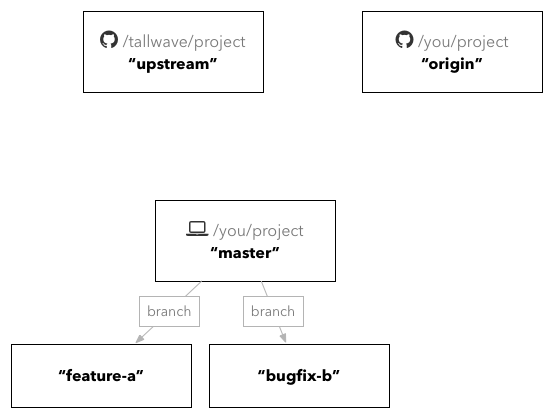

Let’s interrupt real quick and talk naming. The convention here is that the master branch on upstream is what will be deployed at some point. That means that it needs to be in proper working order. Do not commit directly to master and do not push directly to upstream. Do your branching on your own fork (origin) in order to keep upstream clean.

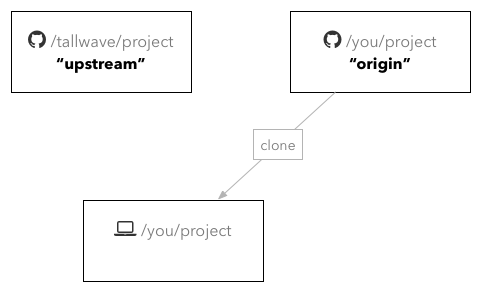

- Clone it to your local machine.

- Create branches for features and bugfixes. These should be intelligently named and end with the issue number, preceeded by a hash (#).

spline-reticulator-#11orfix-data-deletion-#23are good.fixesis bad.

- Commit early and often. Commit messages should also be intelligent and describe what changed. It is recommended taking the present tense with commit messages, so that it completes this sentence: "This commit...".

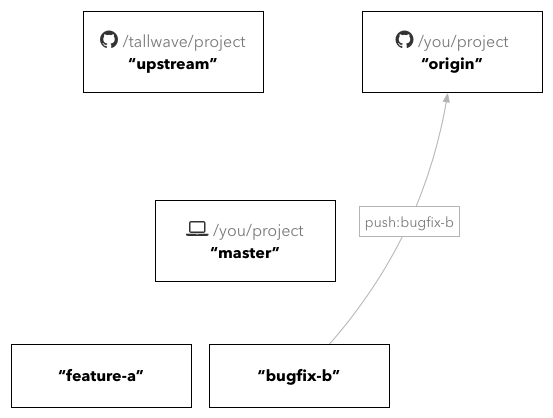

- Push the commits to that branch on

origin(remember this is your fork)

- When ready, create a Pull Request (or Merge Request on Gitlab). This should have a good title and descriptive message.

- The developer should assign another developer (or more) to review the PR.

- Reviewers can comment on code, request changes, or approve the PR.

- Once approved, the PR can be merged into the

masterbranch. - Others can then pull from

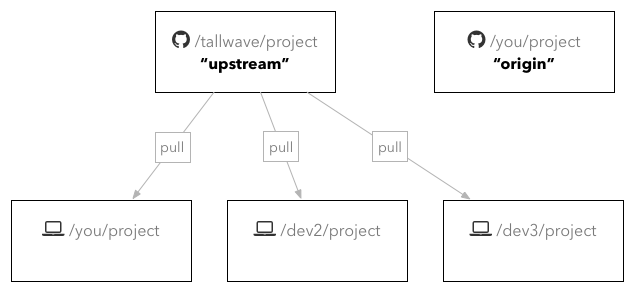

upstreamto get the most up to date code.

You’ll be doing git pull upstream master a lot in order to stay up to date. Frequent smaller commits also helps avoid conflicts.